Well, hello there! You just caught me cogitating and ruminating over the fact that so many things that seem conceptually simple when you are first exposed to them turn out to have hidden depths of complexity when you consider them more closely.

Take Newtonian gravity, for example. In his Law of Universal Gravitation (1687), Isaac Newton proposed that every mass attracts every other mass with a force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them.

This appears to be easy-peasy lemon squeezy at first sight. For two objects (like the Earth and the Sun), Newtonian mechanics provides neat, exact solutions, with the objects moving in one of the four predictable conic-section orbits: circles, ellipses, parabolas, or hyperbolas.

However, when a third mass is introduced (e.g., Sun, Earth, and Moon), then we have what’s known as the 3-Body Problem. The math becomes far more complex, and there is no general closed-form solution. The object’s motions can be chaotic (small changes in initial conditions can lead to significantly different outcomes) and unstable (one of the bodies may end up being ejected from the system).

How about our own solar system with eight planets (and Pluto)? Suffice it to say that there’s strong evidence the solar system used to look quite different in its early days (~4 billion years ago), with at least one more ice giant planet similar to Uranus and Neptune, and several smaller rocky planets like Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. Where are they now? It’s probably best not to ask.

What about printed circuit boards (PCBs)? Let’s focus just on the shape aspect of these little scamps. I tend to think of boards as being rectangular, with perhaps the occasional indent or outdent to accommodate something like a connector. That’s pretty simple, right?

Well, as I was in the process of penning this piece, a friend, whom we will call John (because that’s his name), sent me a link to this article about how researchers are exploring traditional Japanese paper folding (origami) and paper cutting (kirigami) techniques to create kiri-origami printed circuit structures.

As an aside, in high school (way back in the mists of time when wild poodles roamed the Earth), I was in the same class as Nick Robinson, a world-renowned origami artist, educator, and author, with over 100 books to his name. This just goes to show that life sometimes unfolds (or folds) in unexpected directions, but we digress…

What? You want one more example? Well, of course, I’m happy to oblige.

When you first hear about DNA, the concept seems almost disarmingly simple. There’s the famous double helix — a twisted ladder formed by two sugar-phosphate backbones, with rungs made from four chemical bases: adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C), and thymine (T).

If we think of those rungs as letters, then they’re grouped into three-letter words called codons. Genes are specific sequences of these codons. Through two processes—transcription (DNA to RNA) and translation (RNA to protein)—genes are used to construct proteins, long chains of amino acids that carry out the work of life. Each codon corresponds (roughly speaking) to an amino acid “building block” in the protein.

For a time, it was assumed that each gene in an organism’s genome (the complete set of DNA instructions) corresponded neatly to a trait in that organism’s phenotype (the full set of observable characteristics: height, eye color, behavior, physiology).

Oh, that it were so simple. We now know that only about 2% of our DNA actually encodes proteins; the rest remains something of a mystery. Even more humbling, the human genome contains just 20,000–22,000 protein-coding genes—fewer than a banana, which boasts around 30,000. The fact that these little rascals can give rise to something as awe-inspiring as me (and, I suppose, you too) truly boggles the mind.

I’m currently working my way through How Life Works by Philip Ball, and it’s dizzying how much more complicated things really are. Human genes are chopped into exons (coding segments) and introns (non-coding ones). When a gene is transcribed, its exons can be stitched together in different ways—a process called “alternative splicing.” This means that a single gene can give rise to multiple messenger RNAs, which in turn can produce multiple proteins.

And it gets stranger still. Knock out what looks like a crucial gene, and often the cell, or even the whole organism, carries on as if nothing happened. There’s no one-to-one mapping between gene and trait; instead, it’s more like a swirling “soup” of interactions, with chains of causality and networks of proteins influencing one another in subtle, overlapping ways… and then things start to get complicated.

The reason I’ve been waffling about the earlier stuff is that I was just introduced to another idea that sounds simple until you “look under the hood”—turning trained AI models into deployable inference engines through quantization.

I’ve just been chatting with the two co-founders of a startup called CLIKA—Nayul Lina Kim (CEO) and Ben Asaf (CTO). What follows is my take on what they’re doing (any mistakes are my own).

AI models are built from artificial neural networks (ANNs). Like their biological counterparts, each artificial “neuron” aggregates inputs from many others. Each input carries a “weight” (coefficient)—positive weights tend to increase a neuron’s output (excitatory), negative weights tend to decrease it (inhibitory). The neuron combines these weighted inputs, applies an activation, and passes the result onward.

ANNs stack into hundreds or thousands of layers, and modern LLMs can have tens of billions of parameters (weights). Models are commonly trained with weights and activations in floating-point (historically FP32; nowadays often FP16/BF16). For deployment, these values are quantized to lower precision—such as INT16, INT8, or INT4—and different layers may require different bit widths.

Here’s the catch: just as in biology, there are non-obvious chains of causality. A seemingly harmless change in one layer can ripple downstream and negatively impact accuracy elsewhere.

Traditionally, there are two paths to compression: post-training quantization (PTQ), which converts a trained model to lower precision after training (this is fast and data-light, but accuracy can dip), and quantization-aware training (QAT), which simulates quantization during fine-tuning so the model adapts (this usually preserves accuracy under aggressive compression, but demands extra compute and carefully curated data).

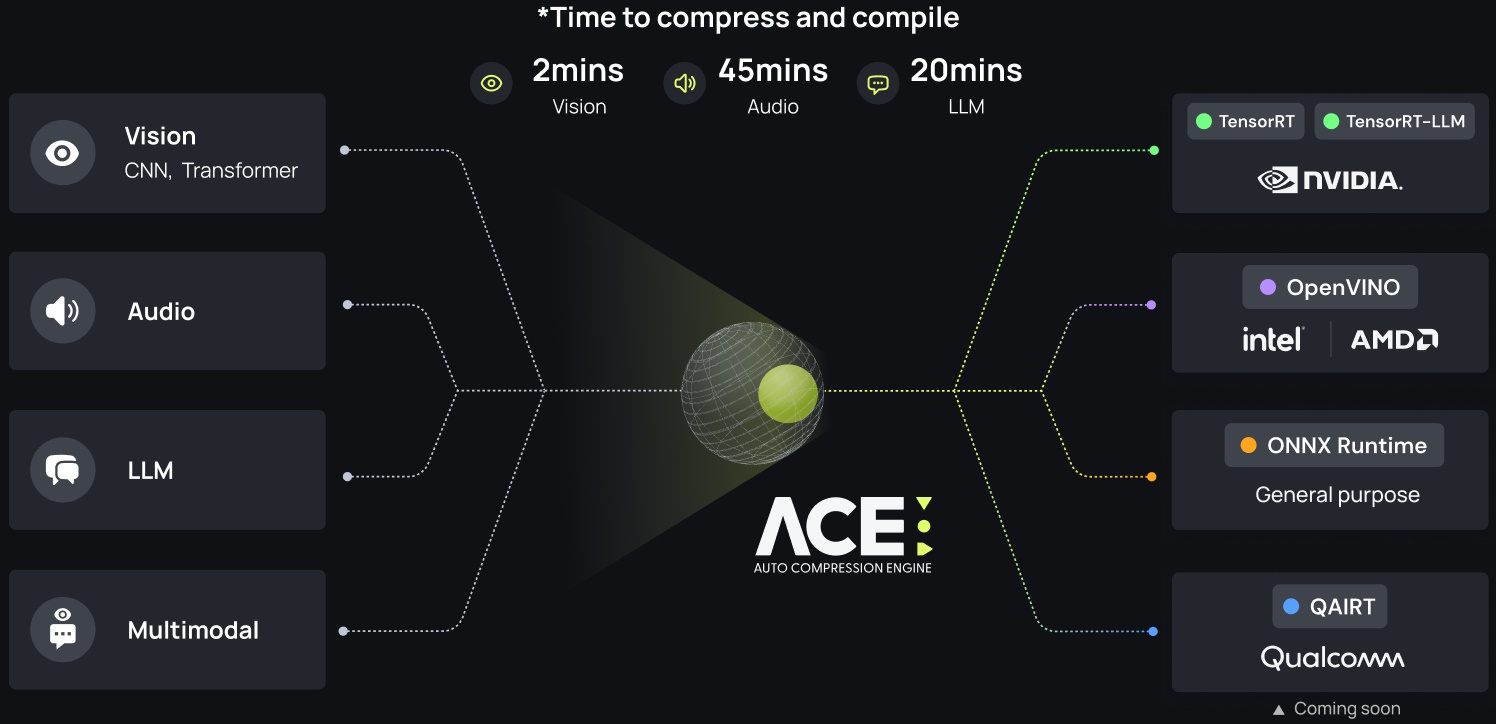

CLIKA’s Automatic Compression Engine (ACE) supports both PTQ and QAT across model families (including generative AI and agentic AI). Their differentiator is a focus on quantization sensitivity (QS), or what I like to think of as sensitivity-aware quantization (SAQ).

ACE scans a model to gauge how much “damage” each region can tolerate, then assigns mixed precision accordingly—FP16 here, INT8 there, INT4 where safe—and skips “offender” layers whose quantization would crater accuracy. It applies this to weights and activations, layer by layer, guided by sensitivity rather than a one-size-fits-all bit budget.

Crucially, ACE aims for push-button automation. You feed in the original model, pick a target device, and press “GO.” CLIKA handles the graph cleanup (layer fusion-removal-replacement), compression, and format conversion for the chosen hardware—no endless hand-tuning loops, no spelunking vendor op-support tables, no weeks of wading through pipeline glue.

CLIKA itself is still young. The company was founded just a few short years ago, and the team has been working furiously ever since. Along the way, they’ve had plenty of tempting offers to divert into side projects, but they kept their heads down and concentrated on their core mission: automating model compression and deployment.

They’ve never really been in “stealth mode” per se, but nor have they been broadcasting their work to the world. Only recently have they begun discussing openly what they’ve built — and they’re already collaborating with government agencies and enterprise-level companies. This early validation suggests they’ve been solving a problem many people feel acutely, but few know how to fix.

So, just like gravity, DNA, and even the humble circuit board, AI model optimization looks simple at first glance but hides a world of hidden complexity (and you thought I couldn’t tie everything together—for shame!). Thankfully, in the case of AI model optimization, CLIKA has done the hard work of taming that complexity and boiling it down to a single push-button operation. If this sounds like the kind of magic you’d like to have working for you, then feel free to reach out to the folks at CLIKA to learn more (tell them “Max says hi!”).